By Reclaim the American Dream 2016

Over the last three decades, we Americans have lost something precious and essential in our concept of capitalism – the idea that shared prosperity is smart business and smart economics because it generates long-term economic growth and competitiveness for the nation as a whole.

In our recent untrammeled pursuit of cutting costs, cutting corners and maximizing short-term corporate profits, we have plunged our economy into the financial collapse of 2008, spawned disasters like the fatal BP oil rig explosion in the Gulf of Mexico, and created what Citibank has called the greatest economic inequality of any major power since 16th Century Spain.

In the 2016 presidential campaign, both Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Bernie Sanders exposed widespread voter anger at the hyper-concentraiton of wealth and power in America with their attacks on the unfairness of Corporate America’s trickle down economics, of U.S. trade agreements that generated huge business profits but saw several million middle class jobs shipped overseas, and the short shrift given middle class employees by much of American business.

Indeed, the so-called New Economics of the last three decades have left the great mass of middle class American families worse off financially today than in 1999, trapped in stagnant growth, while Wall Street soars to record levels and an economic elite captures a near-record share of the nation’s income.

That is not the way American capitalism used to operate.

When the U.S. Middle Class Was the Envy of the World

Three decades ago, we were the unrivaled “land of opportunity.” Americans could rise up the economic ladder more easily than people anywhere else. We mocked class-ridden Old Europe as an outdated bastion of inequality and aristocratic privilege.

Today, the roles are reversed. The U.S. is no longer the land of opportunity. Studies show that moving up is easier in Germany, France, Scandinavia, Canada, Australia and New Zealand than in the U.S. And the hyper concentration of wealth and power in America today is far more extreme than in other advanced countries.

In our earlier, more democratic version of capitalism from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970s, we as a nation generated widely shared prosperity that made the U.S. middle class the envy of the world. In his famous “kitchen debate” of 1959, then-Vice President Richard Nixon outdid Soviet Communist Party Leader Nikita Khrushchev by declaring that it was America’s democratic market economy, not communism, which had achieved a “classless society.”

That was an exaggeration, of course, but Nixon had hit on something essential. In ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s America, the distance between the top, middle and bottom of the economic pyramid was not so great. Describing that period, economists coined the term “Great Convergence” – meaning convergence of income levels.

Inclusive capitalism- Sharing the Gains

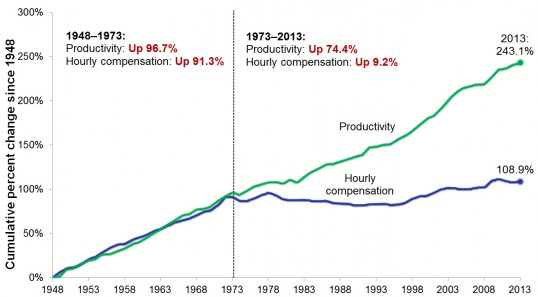

One basic reason for the shared prosperity of the postwar era was that the gains in American economic growth and efficiency got passed through to average Americans. From 1945 to 1975, the productivity of the American workforce roughly doubled. Productivity rose nearly 97% and the median hourly wage and benefits went up 91%. In short, the rising tide was truly lifting all boats.

In that era, CEOs of America’s corporations did not pay themselves vast sums of company stock, as they do today. That was frowned upon as unethical insider trading, because obviously top corporate executives have inside information on new products about to appear or other major moves on the horizon.

So the annual salary of business leaders such as Charlie Wilson, then CEO of General Motors, was equal to $5 million in today’s money, low pay by modern standards. Wilson made about 30-40 times the annual salary of an average autoworker, far below the ratios of 250-1 or 300-1 seen today.

What’s more, GM not only paid good wages to its middle class workforce, it provided good health and retirement benefits. And GM was not alone. It was the business model followed by many other American companies.

High Wages and Henry Ford

What is striking about the shared prosperity achieved from 1945 to 1980 is that American capitalism was then powered by a crucially important idea – the idea that high wages and salaries for average workers are the engine of economic growth for all, for the nation as a whole.

Henry Ford was actually the first mass practitioner of that business philosophy. In 1914, when Ford brought out the famous Model T car, he made the stunning announcement that he was doubling the pay of Ford Motor Company’s autoworkers to the then unheard-of wage of $5 a day.

To Ford, paying his workers well was not only fair but smart business. “ A low-wage business is always insecure,” Ford Said. He meant when wages are low, business is slow and economic growth is weak because customers don’t have much money to spend. But when pay is high, consumers have more spending money and business prospers.

So by paying Ford workers $5 a day, Ford hoped more of them could afford to buy his Model T cars.

“The Virtuous Circle of Growth”

Henry Ford had put his finger on what modern economists call “the virtuous circle of growth” – the insight that when most American companies pay high wages to tens of millions of middle class workers, it benefits the whole economy. High wages create strong consumer demand and that drives economic growth. It pushes business to expand, build new plants, buy new technologies, hire more workers.

Each expansion generates a new round of consumer demand. The virtuous circle is the gift that keeps on giving. It keeps on generating growth, unless someone mistakenly breaks the chain reaction, as has happened in recent decades.

During the heyday of the American middle class in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s, American corporate leaders believed in “the virtuous circle.” They saw a competitive advantage in caring for their workforce. To expand and to generate steady profits, they worked to keep loyal, moderately skilled, well motivated employees on their payroll. The key was assuring good steady jobs with rising pay and benefits.

Stakeholder Capitalism

Frank Abrams, chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey, was among those who voiced the corporate manta of what many economists call “stakeholder capitalism.” Abrams said the CEO’s goal, his moral responsibility, was “to maintain an equitable and working balance among the claims of the various directly affected interest groups …stockholders, employees, customers, and the public at large.”

William Robinson, chairman of Coca-Cola, asserted that a corporate leader must serve not only stockholders but also workers, customers and the larger community. “The neglect of the customers and his labor relations will seal his doom far faster than an avaricious quick-dollar stockholder or director,” Robinson said.

General Electric’s manager of employee benefits, Earl Willis, explicitly linked corporate success to worker security. “Maximizing employment security is a prime company goal,” Willis declared. ”The employee who can plan his economic future with reasonable certainty is an employer’s most productive asset.”

The Rise of Wedge Economics

That more generous version of American capitalism began to unravel in the late 1970s. No longer did U.S. economic growth and productivity deliver a rising standard of living for average Americans. Labor productivity rose roughly 74% from 1973 to 2013, but the median hourly pay and benefits of the typical U.S. worker edged up less than 9%. Over that time span, a sharply increasing share of the nation’s wealth got concentrated at the top, as America’s corporate leaders embraced a more selfish version of capitalism and simultaneously captured the political power to lobby Congress to write tax laws and policies in favor of business and the super-rich.

The intellectual seeds of this seminal shift were sown by Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago. In his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom and a New York Times magazine essay in 1970, Friedman aggressively attacked stakeholder capitalism, castigating the notion that CEOs should consider any “social responsibilities” beyond maximizing profits to shareholders.

“There is one and only one social responsibility in business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits,” Friedman declared.

Whether Friedman intended it or not, his concept of “shareholder capitalism” spawned the explosion of wedge economics in America – the greatest income inequality and hyper-concentration of wealth in American history. It has opened a yawning gulf in the American economy, with the incomes of the corporate elite soaring into a new stratosphere while most of the middle class is stuck in long-term wage stagnation.

CEO Pay Goes Through the Roof

An academic disciple of Friedman, Harvard Business School Professor Michael Jensen, put flesh and blood on Friedman’s “shareholder capitalism” with a scheme called “pay for performance.” Jensen argued that the best way to motivate CEOs to put their single-minded focus on maximizing return to shareholders was to pay CEOs and senior management primarily with stock – massive grants and options of company shares.

Not surprisingly, that idea was a big hit in corporate boardrooms, especially since back then company shares were not counted as a cost item on the company books. Executive pay packages went through the roof.

In 2005, The Wall Street Journal compiled a list of top ten CEO pay packages since 1995. Oracle CEO Larry Ellison came out No. 1 with $706.1 million in a single year. Close behind were Michael Eisner, former CEO of Disney, with $575.6 million in one year; and Sandy Weill, former Citigroup CEO, who pulled down $621.8 million in three big years between 1997 and 2000. Later, in 2011, Apple CEO Tim Cook took home $378 million, which was 6,258 times the average Apple employee’s pay.

CEOs and their boards became so expert at gaming the system that the payouts were manipulated to reward failure as well as success. In 2009, stockholders of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, two major Wall Street investment banks, were left with nothing when the firms went bankrupt. But the top five executives at each bank walked away with a combined total of $2.4 billion in stock options profits and cash bonuses.

By 2002, even Michael Jensen was disillusioned. “Pay for Performance,” Jensen lamented, had become “managerial heroin.” CEOs were hooked on it. But by then, it was impossible to change course. The tenets of shareholder capitalism were being taught at all the best business schools, enshrined as the default model of Corporate America.

Shareholder Capitalism = Middle Class Squeeze

Down at the employee level, CEOs decided that the dictates of shareholder capitalism required them to cut costs, freeze wages, shed benefits, downsize, shut plants, move jobs overseas, or keep company headquarters at home but merge with a foreign company to escape paying U.S. taxes.

In short, under shareholder capitalism, American CEOs cut the historic connection between corporate profits and employee income, between rising productivity and middle class living standards. Business leaders simply canceled “the virtuous circle of growth” that had been the secret of widespread prosperity for three decades.

The once matching patterns of rising workforce productivity and a rising middle class standard of living began to diverge in the late 1970s, under shareholder capitalism. From the late 1970s until 2011, productivity roared upward by 80% but the median hourly wage crawled up only 10% – less than one-third of 1% per year over 32 years.

So in 2014 and 2015, as Wall Street celebrated record corporate profits, Main Street stagnated. Typical family income is lower today than in 1999. Since the late 1970s, 84% of the income gains of our entire nation have gone to the top 1%. America’s super rich rake in more income than entire countries like France, Italy or Canada.

Wal-Mart Epitomizes Shareholder Capitalism

You can see the change in individual companies. Today, Wal-Mart epitomizes shareholder capitalism, replacing General Motors as the nation’s business model.

In place of GM’s high wages, steady jobs, and good benefits, Wal-Mart’s formula is low wages, low benefits, part-time jobs, high turnover, and a high return to shareholders. Its founder, Sam Walton, was nicknamed “Mr. Cheap.” Even after Wal-Mart promised a pay increase for its lowest paid workers in early 2015, some still qualify for anti-poverty programs like food stamps and Medicaid.

But its shareholders are richly rewarded and its ownership is highly concentrated. The Walton family, heirs to founder Sam Walton, own more than half of Wal-Mart stock. Today, the Walton family incudes four of the nation’s 12 richest people and the family as a whole owns more wealth than the total assets of the bottom 40% of the U.S. population – 120 million people.

The High Cost to America – Slow Growth

The huge inequality gap spawned by shareholder capitalism exacts a high cost on our nation’s economy. It turns out, as Henry Ford suspected, today’s steep income inequality is a drag on growth. That dark reality is now documented by multiple economic studies. The evidence, as one economist put it, is “impressively unambiguous.”

The reasons are not hard to grasp. As Henry Ford and other stakeholder CEOs understood, high wages mean high growth and low wages mean low growth. Well-paid middle class Americans spend what they earn, but the super-rich spend a far smaller percentage. So high income inequality hurts consumer demand – the engine of growth.

Shareholder capitalism hurts in another way. It has crippled the ability of U.S. corporations to invest heavily in their own growth. Since 2000, American CEOs and corporate boards have allocated $3 trillion of company profits to buying back shares of company stock, giving themselves huge pay increases but leaving their companies with less capital to spend on growth.

For Strong Growth, Re-Invent Inclusive Capitalism

Trillions of dollars that could have been spent on innovation and job creation in the U.S. economy over the past three decades have instead been used to buy back (company) shares for what is effectively stock-price manipulation,” economist William Lazonick reported in the Harvard Business Review in late 2014.

The contrast between what business does today and what it used to do is stunning. In a study of hundreds of major U.S. companies, Lazonick found that in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, major U.S. companies ploughed close to half of their profits into expanding their businesses, funding R&D, retraining workers and paying them more, and paid out the other half of profits to shareholders.

But from 2003 to 2012, Lazonick found, shareholders got 91% of corporate profits and growth got only 9%. That is a disastrous ratio the American economy.

“The Dumbest Idea in the World”

In a column headlined: “How the Cult of Shareholder Value Wrecked American Business,” veteran Washington Post business columnist Steve Pearlstein wrote: “In the recent history of management ideas, few have had a more profound — or pernicious — effect than the one that says corporations should be run in a manner that ‘maximizes shareholder value.’”

And after the 2008 Wall Street collapse, former General Electric CEO Jack Welch, an iconic standard bearer of shareholder capitalism in the 1990s, told The Financial Times that on reflection, he thought “shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world.”

So to get back on track to strong, steady economic growth, global competitiveness and more broadly shared prosperity, some economists, high profile business leaders and political candidates from Bernie Sanders on the left to Donald Trump on the right tell us we need to fix American capitalism to make it more inclusive so that more of the economic gains that have been going to Wall Street and wealthy stockholders are shared with middle class workers.